Introduction: From Climate Commitments to Process Reality

Introduction: From Climate Commitments to Process Reality

At COP30, critical minerals shifted from a minor issue to a key element within climate talks. Experts now work in a setting where goals for reducing carbon, plans for electrification, and government support for industry all focus on one main concern: whether mineral supply lines can actually support the speed of the energy shift. Materials like lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements are no longer seen just as goods. They have turned into essential resources whose supply, processing performance, and impact on the environment affect the trustworthiness of paths to net-zero emissions.

In this situation, technical limits count as much as bold policy goals. Although COP30 talks stressed funding options, risks from global politics, and ways to spread out sources, much less focus went to the systems that turn ore into useful materials. However, for professionals or researchers, these systems decide if supply forecasts can hold up under real operating pressure.

This is where NHD holds a unique place. Instead of presenting itself as a player in climate or policy matters, NHD has earned its importance through years of work in the most sensitive parts of mineral processing: solid–liquid separation, slurry preparation, thickening, and heavy-duty mixing. Its equipment has been used in projects for phosphate chemicals, non-ferrous metals, alumina, laterite nickel, and rare earth hydrometallurgy. These projects often depend on steady performance in harsh conditions involving corrosion, abrasion, or high volume.

For practitioners, the value of NHD comes from its practical role rather than marketing. When critical minerals are described as a limit at COP30, the issue becomes concrete. It turns into a question of whether processing systems can keep up output, water savings, and dependability at large scale, over extended runs, and with stricter rules on the environment.

Why Did COP30 Place Critical Minerals at the Center of the Climate Agenda?

How Energy Transition Targets Depend on Mineral Processing Capacity

COP30 showed a change in approach. Negotiators began to connect mineral supply straight to schedules for rolling out batteries, power networks, and renewable setups, instead of treating it as an early-stage problem. Professionals must now match climate plans with actual limits on production volume.

Scenarios for energy transition expect rapid increases in mineral production. Yet, mining alone does not provide ready materials. Losses during processing, limits on water, and stops in equipment operation all add to supply dangers. For instance, small gains in filtering performance or slurry steadiness can lead to huge extra output each year across entire systems.

From this view, COP30 quietly accepted that processing ability, rather than available ore, might become the main limit. For specialists in mineral engineering, this matches what they have noticed for years: steady metal recovery often decides if deposits can be profitably mined.

Why Were Critical Minerals Removed From the Final COP30 Text?

How Political Risk Shifted Focus Away From Industrial Execution

Even though critical minerals featured heavily in talks, they did not appear in the final COP30 statement. This absence shows careful political choices instead of questions about technology. Countries that produce minerals stay cautious about rules that might limit their control over resources. Nations that need them avoid firm promises without secure supplies.

For experts, this difference between discussion and agreement highlights a real fact. Worldwide coordination may fall behind demand, so industry and engineering must handle the ups and downs. In such conditions, steady operations serve as a way to lower risks.

When policy agreement remains unclear, processing systems need to provide consistent results on their own. Reliable filtering, predictable handling of solids, and controlled slurry features cut exposure to sudden price changes, new regulations, and breaks in supply. In short, dependable processes take the place of clear policies.

What Risks Now Define Critical Mineral Supply Chains?

How ESG, Water Stress, and Throughput Constraints Intersect

The dangers in critical mineral supply chains grow more connected. Closer checks on the environment raise worries about water use. Requirements for better social and governance standards call for safer waste storage and less refuse. Meanwhile, demands for higher production keep growing.

Professionals must therefore address several limits at once. Greater solids content helps recover water but adds strain on machines. Quicker production raises output yet makes separation less stable. Weak mixing lowers recovery rates, while too much mixing speeds up damage to parts.

These balances put process equipment right at the heart of supply chain strength. Systems built for limited conditions fail when pushed further. On the other hand, equipment made for broad operating ranges can handle changes without major breakdowns.

How Can Processing Technology Reinforce Supply Chain Resilience?

Why Filtration Performance Shapes Downstream Stability

Solid–liquid separation continues to be one of the most important steps in mineral processing. Filtering results directly influence water recycling, waste handling, and material movement. In big critical mineral plants, even minor changes in moisture levels or clarity spread effects to later stages.

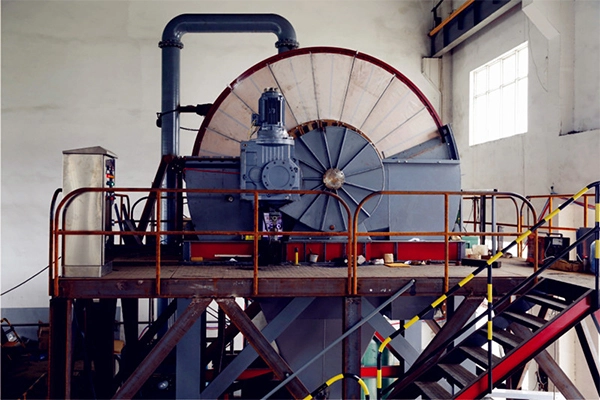

This explains why disc-type filtration has gained renewed interest for tough uses. When built for rough slurries and nonstop work, disc filters deliver steady results despite varying input. In particular, the disc filter from NHD has been installed in phosphate, non-ferrous, and hydrometallurgical lines where extended durability and steady flow are vital.

For specialists, the importance goes beyond choosing equipment. Reliable filtration allows better management of thickening, pumping, and storage. As a result, it lowers overall risk throughout the facility.

How Should You Optimize Mixing and Slurry Conditioning Under Constraint?

Why Agitation Determines Recovery and Equipment Longevity

In critical mineral treatment, slurry properties control how well separation works. Slurry that lacks proper preparation causes uneven spread of chemicals, irregular settling, and unstable filtering. These problems worsen as plants grow larger.

Mixing thus serves a central purpose. It acts as a way to ensure particles contact chemicals and each other in consistent patterns. For non-ferrous and beneficiation lines, mixing needs to balance power use, control of forces, and lasting strength.

The agitator for nonferrous industry and beneficiation created by NHD achieves this balance. Its structure emphasizes even flow patterns and strong build over time. This allows reliable work in thick, harsh settings.

For experts, the benefit comes from consistency. When mixing stays steady, later separation steps become easier to manage. This reduces differences across the entire processing sequence.

What Opportunities Emerge Beyond COP30 Commitments?

How Engineering Execution Will Outpace Policy Alignment

Though COP30 failed to set formal rules for critical minerals, it made expectations clearer. Supply chains need to grow quicker, with less harm to the environment, and fewer breakdowns. In reality, this moves attention to engineering answers that offer quick improvements without needing global agreements.

Demand will likely rise for flexible processing units, technologies that save water in separation, and equipment that works under varied rules. Projects in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia already show this pattern. There, strong engineering makes up for unclear institutions.

In these conditions, processing technology turns into a key advantage. Systems that maintain production during stress effectively lengthen resource life and improve project funding chances.

Conclusion

COP30 highlighted a conflict that experts already know: grand climate plans rely on solid industrial performance. Critical minerals stand where policy, resource location, and engineering meet. Yet, processing dependability ultimately decides supply outcomes.

For researchers and practitioners, the message stands out. The future of critical minerals will not depend only on talks in meeting rooms. It will be decided by how well filters, agitators, and separation units perform day after day, often in remote locations. Closing the space between climate targets and material facts demands ongoing focus on basic process engineering.

FAQs

Q1: Why are critical minerals considered a bottleneck in energy transition scenarios?

A: Because deployment of batteries, grids, and renewables depends not only on reserves but on the ability to process minerals at scale with acceptable environmental and operational performance.

Q2: Why did COP30 avoid formal commitments on critical minerals?

A: Political sensitivity around resource sovereignty and supply chain control led negotiators to prioritise consensus on emissions and finance rather than industrial governance.

Q3: Which processing stages most influence critical mineral supply reliability?

A: Solid–liquid separation, slurry conditioning, and thickening play decisive roles, as they directly affect recovery, water reuse, and downstream stability.